Protobuf — serialization and beyond. Part 4. Data validation

on

In this series, we explore the features and advantages of using Protocol Buffers as a model-building tool. In this part, we take a look at how to validate data with Protobuf and what can be learned from the mechanisms behind data validation.

What is Validation?

When developing a domain model, one often faces a need to enforce certain rules upon the data objects. Strongly-typed languages, such as Java, help us order up data into neat structures and then build Value Objects upon those structures. However, none of the programming languages is expressive enough to form the whole model and enforce all the known rules. This is not a failure of the language designers, but a required tradeoff for creating any sort of general-purpose programming language.

If not solved in a general way, the need to check if the data fits the domain rules leads to conditional statements and exceptions scattered across the codebase. Such a chaotic approach allows errors to pop up once in a while, rendering the system unreliable.

Validation for the rescue

A well-integrated validation mechanism sieves off corrupted (or, often, mistyped) data early in the flow and gives the developers a safety net against small errors.

When talking about validation, we mean the integrity of the individual objects, rather than the whole system. Consider a user account model:

message User {

// ...

EmailAddress primary_email = 7;

}

Checking if the email is set and is a valid email address is a part of the data object validation. Verifying whether the email is unique in the system or such an address already exists, is not a part of the data object validation and is out of scope for this article.

Validation solutions come in many shapes and sizes, but all of them share a common structure. Validation rules, a.k.a. validation constraints, define the axiomatic facts about the data in the system. An evaluator for the constraints checks input data and reports any violations. Typically, the constraints are defined in a declarative DSL, while the evaluator is separated from the constraints for simplicity.

Java Validation Framework

In Java, there is the Bean Validation 2.0, also known as JSR 380. This JSR is a specification that constitutes a set of validation annotations, which allow the programmers to declare validation constraints, and an API for manual invocation of the checks. For example, consider a user account object implemented in Java.

import javax.validation.constraints.Email;

import javax.validation.constraints.NonNull;

import javax.validation.constraints.NotBlank;

class User {

@NotBlank

@NonNull

private String login;

@Email

@NonNull

private String primaryEmail;

// ...

}

String fields are marked with special annotations, such as @NotBlank, @Email, @NonNull to signify that the value must have some non-whitespace characters, must contain a valid email address, and must not be null respectively.

Such an annotation-based approach gives the API users an ability to choose between explicit invocation of the validation process via the runtime API and implicit invocation via manipulating bytecode and inserting corresponding checks right along with the user code.

Validation with Protobuf

We work with Protobuf, a multi-language tool for defining data models. As we use Protobuf for domain modeling, we require a robust built-in mechanism for validation. Unfortunately, Protobuf itself does not supply one. So, we’ve built our own.

Why develop our own validation?

“Everybody has a logging framework, but mine will be better.” — a naïve software engineer.

Indeed, developing something as fundamental as a validation library might seem a bit silly. Aren’t there people who’ve done that before?

There are indeed other validation solutions for Protobuf. Many of them are similar to what we do. Some, just like us, generate validation code. Others rely on runtime validators. What makes the difference is the smooth integration with the generated code itself.

How it works

First things first. The features described in this article apply primarily to the generated Java code. Some features are also implemented for Dart. In the future, we are planning to also cover other languages, such as JavaScript and C/C++. Fortunately, the cost of adding another language is lower than the cost of developing the whole validation tool from the ground up.

Protobuf provides options as a native way to declare the meta-data for each file, message, or field. The options API resembles the JSR 380 annotation API. Such cohesion allows developers familiar with the Java API to get a grip of our options API faster.

Consider the following message:

message LocalDate {

int32 year = 1;

Month month = 2;

int32 day = 3;

}

It’s up to users to define their custom options and then provide some mechanism to deal with them. On top of this feature, we have built an infrastructure for validating Protobuf messages. Validation rules are defined using custom options for fields and messages:

message LocalDate {

int32 year = 1;

Month month = 2 [(required) = true];

int32 day = 3 [(min).value = "1", (max).value = "31"];

}

This example is rather simplistic, as, for example, the max number of days depends on the month and year values in real life. We ignore this fact for now, since there is no easy and robust way of adding complex logic code to Protobuf definitions. In the future, we are planning to allow more complicated scenarios for validation rules. We, however, have not figured out the syntax for such constructs yet.

Our options, such as (required), (pattern), (min), (max), etc., are transpiled into executable code during Protobuf compilation. We embed this validation code directly into the code generated by the Protobuf compiler for the target language.

In the example above, the Protobuf compiler generates a Java class from LocalDate. We add the validate() method into that class. Here is the simplified version of it:

public ImmutableList<ConstraintViolation> validate() {

var violations = ImmutableList.builder();

if (!isMonthSet(msg)) {

violations.add(ConstraintViolation.newBuilder()

.setMsgFormat("A value must be set.")

.setTypeName("spine.time.LocalDate")

.setFieldPath(path("month")))

.build());

}

if (msg.getDay() > 31) {

violations.add(ConstraintViolation.newBuilder()

.setMsgFormat("The number must be ≤ 31.")

.setTypeName("spine.time.LocalDate")

.setFieldValue(msg.getDay())

.setFieldPath(path("day"))

.build());

}

if (msg.getDay() < 1) {

violations.add(ConstraintViolation.newBuilder()

.setMsgFormat("The number must be > 1.")

.setTypeName("spine.time.LocalDate")

.setFieldValue(msg.getDay())

.setFieldPath(path("day"))

.build());

}

violations.addAll(violationsOfCustomConstraints(msg));

return violations.build();

}

Note that we intentionally chose the “eager” validation approach, i.e. we try to collect all possible violations instead of quitting on the first found error.

Users of our Validation library can also extend the standard set of options with the custom definitions. This feature is only supported in Java for now.

Consider the following message:

message Project {

// ...

ZonedDateTime when_created = 4 [(required) = true];

}

The when_created field stores the info about the timestamp of the project creation. It is true that the field must be set, i.e. it always exists in the domain, hence an absence of this value is a technical error. And there’s more to it. We’ll assume that the described project already exists in real life. So, its creation time has to be in the past from now. Let’s introduce an option to signify that. To do so, we extend the standard set of field options with a new one:

import “google/protobuf/descriptor.proto”;

extend google.protobuf.FieldOptions {

WhenOption when = 73819;

}

message WhenOption {

TimeDirection in = 1;

enum TimeDirection {

WOTD_UNDEFINED = 0;

PAST = 1;

FUTURE = 2;

}

}

The field number for the when option is 73819. It is due to how Protobuf distributes field numbers and extensions that we have to use such obscure constants. Read more about field numbers for extension types in this guide and this comment in google/protobuf/descriptor.proto.

Now, we just use the option in the domain:

import “example/validation_options.proto”;

message Project {

// ...

ZonedDateTime when_created = 4 [

(example.when).in = PAST, (required) = true

];

}

The declaration part is ready. It’s time to move to the implementation.

First, we define a constraint:

final class WhenConstraint

extends FieldConstraint<WhenOption>

implements CustomConstraint {

WhenConstraint(TimeOption optionValue,

FieldDeclaration field) {

super(optionValue, field);

}

@Override

public ImmutableList<ConstraintViolation>

validate(MessageValue message) {

// Extract and validate the field value.

}

}

Then, we define the Java wrapper for the Protobuf option. This class is responsible for locating the option and creating the associated constraint.

final class When extends FieldValidatingOption<TimeOption> {

When() {

super(TimeOptionsProto.when);

}

@Override

public Constraint constraintFor(FieldContext value) {

return new WhenConstraint(

optionValue(value),

value.targetDeclaration()

);

}

}

Finally, we implement the ValidatingOptionFactory interface, override the methods in it, returning only new options and only for the necessary field types:

final class When extends FieldValidatingOption

When() {

super(TimeOptionsProto.when);

}

@Override

public Constraint constraintFor(FieldContext value) {

return new WhenConstraint(

optionValue(value),

value.targetDeclaration()

);

}

}

The class WhenFactory has to be exposed to the Java ServiceLoader mechanism as an implementation of ValidatingOptionFactory either manually or via an automatic tool, such as AutoService.

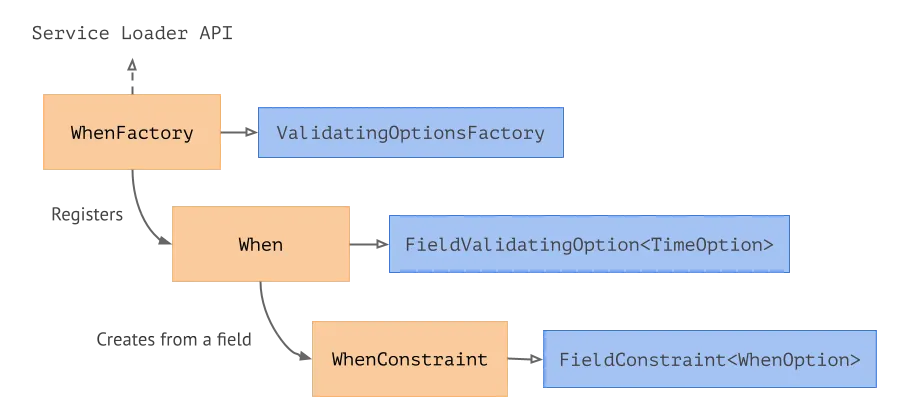

Here is the diagram of the classes we’ve just described.

We expose the WhenFactory, which implements theValidatingOptionFactory, via the ServiceLoader API. WhenFactory registers the When option, which, when necessary, creates a WhenConstraint based on a field definition.

On the diagram above, the amber components are what the user implements and the blue components are the interfaces provided by the Validation library.

The (when) option is already a part of the Spine Validation library. Users don’t have to redefine it on their own.

Protobuf required: Il buono, il brutto, il cattivo

A reader familiar with the differences between Protobuf v2 and v3 may have noticed and been surprised by the required term in the example defining the Project type shown above.

In Protobuf version 2, any field could be marked as required or optional. Later, the library creators declared this approach to be more harmful than good. In Protobuf version 3 and its analogs, all fields are always regarded as optional. The reason for this is binary compatibility. The required field in Protobuf 2 cannot be made optional and vice versa without breaking compatibility with previous versions of the message. For a serialization and data transfer tool, this is a big issue, as different components that communicate with each other using Protobuf messages may use different versions of those messages. Breaking binary compatibility means breaking such communications.

Seems like the effect of using required is a net negative one. Why bring it back?

In our Validation library, we decided to partially revive the required monster. We need to describe the requirements for data values in the domain model. Some fields are required by nature. Of course, it may change with the model development. But, unlike the Protobuf v2’s built-in required keyword, our option (required) works at the validation level, not at the level of the communication protocol. It means that invalid messages can still be transmitted and serialized/deserialized. It is the programmer’s decision whether to use or ignore validation in each case.

For example, in Java, to create a non-validated message, we use the buildPartial() method instead of the regular build(). This method was introduced in Protobuf 2 in order to build messages and skip checking the required fields. We expanded this notion to state that the whole message may not be valid when built using buildPartial().

A technical note. In Protobuf 2, all fields had to be declared as either required or optional. In Protobuf 3, all fields are optional. In the fresh Protobuf 3, in v3.15 to be precise, the keyword optional was brought back. Though, the semantics of this keyword is different this time around. The Protobuf 3 optional allows users to check if the field is set, even if it’s a number of a bool field. Not to be confused with ye olde optional fields of Protobuf 2.

Proto Reflection

Under the hood, our Validation library uses the Protobuf reflection API in order to obtain the message metadata. When a .proto file is compiled into target languages, the compiler exposes the metadata in a form of Protobuf messages known as descriptors. Descriptors contain information about the entire scope of the Protobuf definitions, from message fields to the documentation. It also includes the options defined on the messages and fields.

In some target languages, a descriptor can also be obtained at runtime. For example, in Java, every message class “knows” about the associated descriptor:

Descriptor type = MyType.getDescriptor();

Unfortunately, there is no analogous API in other target languages, such as JavaScript and Dart. Fortunately, the descriptors are always available at compile time. Users are welcome to add their own Protobuf compiler plugins to access the descriptors and generate code based on them.

More on Code Generation

As of the time of writing, we are working on a new mechanism for code generation, which will also change the internals of how we generate validation code. We thought we might share it here.

The new tool we’re working on is called ProtoData. It allows reducing the effort of generating code for multiple platforms. Descriptors in the Protobuf compiler are a language-agnostic intermediate representation of the Proto definitions. For our code generation, we also build a language-agnostic model, based on the Protobuf definitions. And then feed those representations to multiple language-specific renderers, which turn them into code.

The whole tool is built on an event-driven architecture, which allows users to tap into the generation process in a simple and non-intrusive way.

Right now, we’re approaching the first public release and an API freeze for the tool. If you would like to explore it, visit the GitHub repo.

Conclusion

Protobuf provides a great variety of choices for how to use it. In its simplest form, Protobuf is a serialization format. But due to the systematic and future-proof approach used by the designers of the technology, it has become much more than that.

Protobuf reflection API, which is, originally based on Protobuf types itself, allows users to bend and stretch the technology to great extent. Access to the meta-data and entry points for quick code generation enabled us to create an entire validation library based on Protobuf definitions without a need to parse the definitions on our own or to do heavy operations on metadata at runtime.

A validation library is just another step towards an expressive and resilient domain model. And with our Validation library and Protobuf, we make this step a commodity.

In the next part of this series, we will build on top of what we have already learned and tried by looking at domain modeling. We will explore different kinds of messages, see how validation integrates into the information flow, and discover the hidden benefits of using Protobuf for a domain model.